Entering the War

Following the bombing of Kassa on the 26th June 1941 Hungary declared war on the Soviet Union. There is still no satisfactory answer to the question of who launched this attack. Nor can our Webpage give a certain answer to this, however we will try to give you a clearer picture by explaining who it is believed was not responsible.

A day after the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, on the 22nd June 1942, József Kristóffy, Hungarian Ambassador in Moscow, sent the following telegram to the Foreign Ministry in Budapest ‘Molotov summoned me this morning. He asked me about the position of Hungary in the current German-Soviet conflict and informed me that the Soviet government, as previously declared, has no claim or hostile intention towards Hungary. He had no objection to Hungarian territorial claims in Romania [Transylvania] and added that they will have no such objection in the future. Due to the fast moving situation, the Soviet government needs to know as soon as possible if Hungary has any intention of participating in this war or would prefer to remain neutral. I informed him that I cannot answer without the authorisation of my government. Molotov requires an immediate answer I await your earliest response’.[1] Receiving no answer, according to his daughter he resent the telegram to Budapest three or four times that evening.[2] By this time Romania had already declared war on the Soviet Union. Bessarabia, a territory between the River Don and the Danube delta under Romanian authority from the 14th Century, was occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940, due to this loss Romania was considered one of the most determined of Moscow’s enemies. This deep-rooted hostility between Moscow and Bucharest gave Molotov’s promises regarding Transylvania credibility. The situation was turned on its head by 1947. Romania ended up on the victorious side of the war together with the Soviet Union. During peace negotiations in Paris, the Soviet Union allowed Romania to annex Transylvania in exchange for their continued presence in Bessarabia. Hungary lost north Transylvania which it had regained in 1940 by the grace of Italy and Germany in the Second Vienna Award.

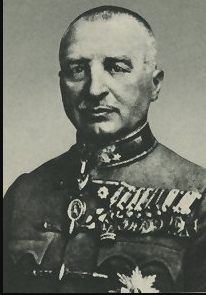

In the early summer of 1941, weeks before Operation Barbarossa, the Hungarian General Staff and especially its commander, General Henrik Werth, who had been in receipt of regular correspondence from German army leaders, had been urging the government to take part in the forthcoming operations of the Reich. Werth compiled two memoranda for Prime Minister László Bárdossy but failed to convince him that Hungary should join the war as soon as possible and before those neighbouring states with which it had a tense relationship. Bárdossy, with the intention of following the foreign policy of his predecessor, Pál Teleki, acted according to his main principle of preserving the Hungarian army until the final stage of the European war. Hungary was surrounded by hostile states and the most likely endgame would be war with Romania.[3]

In a meeting of the government on the 23rd of June the Prime Minister proposed that they pre-empt any German request to join the war by breaking their diplomatic relationship with the Soviet Union. The document declaring this action could have been communicated to the Germans in the future as a declaration of war - as happened with the Hungarian declaration of war with the USA in December 1941. However, there was no request from the Germans as the political leadership of the Reich was aware that they could make Hungary join the war only with further territorial promises and, as Romania was one of their most useful allies - because of its position and its oilfields - it was not in their interest to do so[4].

A day before, Otto Erdmannsdorf, Ambassador of the Third Reich, had handed the Regent a letter from Hitler in which the Führer did not even mention that the Germans would expect the support of the Hungarian army in the current operation, ‘Your Serene Highness, I would like to express my gratitude for the simple act of your Army’s defence of Hungary’s borders keeping Soviet forces at bay and undermining their attacks on our flanks.’[5]

Receiving the decision of the government, Henrik Werth turned to the Germans for support. On the same day, June 23rd, he contacted General Kurt Himer, liaison officer for the German and Hungarian armies, and asked him if the statements of the German political leadership should be understood to say that Germany did not desire Hungarian participation in the war against the Soviet Union. The answer arrived that evening from Colonel General Alfred Jodel of the general staff of OKW: ‘we accept all Hungarian support. We ask nothing but are open to all offers. There is no question that we are not against a possible participation with Hungary.’ On the same day, General Werth visited Regent Horthy in Kenderes and attempted to convince him of the necessity of entering the war.[6] Meanwhile, Prime Minister László Bárdossy, not entirely confident of the decision of his government, sent Major General Antal Náray to take soundings at the headquarters of the General Staff as to the possible outcome of the war. Colonel General Elemér Sáska urged Náray to convince the Prime Minister to join the war.[7]

On the 24th June Werth submitted a further memo, on receipt of which Bárdossy called a second meeting of the cabinet. He was indignant that the head of the General Staff would question the government’s competence.[8] As the head of the Foreign Ministry Press Office, Antal Ullein-Reviczky, later recalled, Bardossy went pale when he read the memo and hit the table with his fist saying ’we have nothing to do with this war, this is not our war.’[9] The day after the start of the German operation increased activity of the Soviet Air Force was observed in the Tisza valley near the Hungarian border. During these operations Soviet aircraft occasionally entered Hungarian airspace – but this was in error.

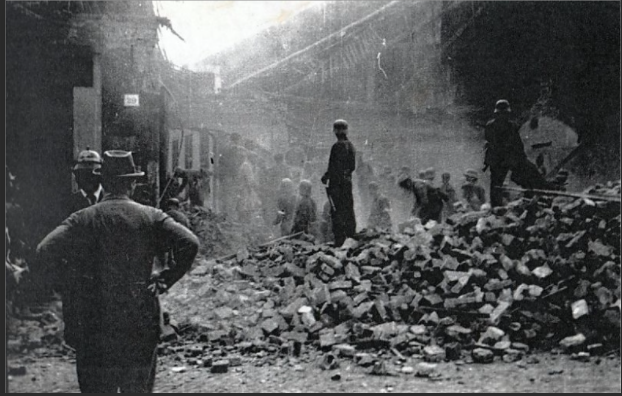

On the 26th June Air Defence Centre [Kassa] VIII reported several incursions on the Hungarian border by Soviet aircraft. In the early hours Soviet planes were observed in pursuit of three German aircraft over Kisszolyva. At 7.10 am six, single-engined Soviet craft crossed the border at Volóc returning via Alsóverecke, one of which strafed a deserted Hungarian air defence base. At midday, probably mistaking it for a German military train, three Russian aircraft bombed the Hungarian express leaving Budapest for Körösmező. This was just over an hour before the bombing of Kassa. At 3.25pm the air defence of Munkács and Ungvár observed a number of single Soviet aircraft flying westwards.[10] It is worth noting that all of these were considered by the air defence base of Kassa as normal in the prevailing war situation and didn’t even report to the National Centre of Hungarian Air Defence before the end of the day and then only after the bombing of Kassa and in that context. None of these Soviet attacks was denied by the Soviet military leadership, however they firmly denied the bombing of Kassa at the time and ever since.[11] A feature of all the incursions on the 26th June was that they were all carried out by Soviet aircraft with clearly identifiable insignia. The bombing of Kassa began at 3.08pm. As is usual of witnesses to such events their accounts were contradictory, most of them recalled three aircraft flying in an arrowhead formation but some of them reported having seen four.[12] They couldn’t even agree as to whether the aircraft had a painted yellow ring which was usual on aircraft of airforces in the Axis.[13] The only thing that is the same in every account is that the aircraft had no insignia.

Following the training on that day, Ádám Krúdy, commander of the Air Academy, was flying an Arado 79 training plane on a final circuit above Kassa ’just for fun’ with two of his colleagues. Flying southwards they met a formation of four aircraft without insignia and, because of the formation which was usual for the Wehrmacht ’we thought that they were German aircraft returning from a sortie and intending to refuel – until they started to release their bombs’.[14] According to Béla Fejér commander of the mobile Anti-Aircraft Unit 17, three aircraft without isignia entered our airspace approaching from our right. We had received no warning, when I saw the bombs falling I gave the order to attack.’ Colonel János Héderváry –Konth of the 2nd company of the VIII Signal Corps in Kassa said the ’aircraft were sandy-coloured and twin-engined, however their identity couldn’t be confirmed because neither their wings nor their fuselage carried any insignia, it was only from the shape of the wings that we suspected they were Avia planes of the former Czechoslovakia.’[15]

In 1981, in Oshawa, Canada, József Ledényi, an officer of the Air Defence headquarters in Kassa, told József Ormay, former lieutenant of the Hungarian Air Force, that ’they couldn’t be mistaken for our aircraft, they sounded quite different, they were khaki coloured without any insignia.

Ormay: Were you looking for the insignia on them?

Ledényi: Yes, we looked but there weren’t any insignia on them, they were at approximately 1500m.

Ormay: Did you see colours on them?

Ledényi: Yellow, on the fuselage, a yellow ring could be seen, but it wasn’t an insignia.

Ormay: Was there any colour on their wings?

Ledényi: There wasn’t any, the whole aircraft was khaki, they were twin-engined.

Ormay: They weren’t Hungarian or German?

Ledényi: No way.

According to János Szabó, an agricultural land surveyor, they were short and solid, brownish aircraft without insignia or any other identifying features.[16] As can be seen, all the testimonies report aircraft without insignia and not aircraft with unrecognisable insignia due to poor weather conditions, as was stated in the official communiqué of the Kassa Air Defence and written a day after the bombing, when Hungary was already at war with the Soviet Union as a result of this attack. In addition, we have the evidence of Ádám Krúdy’s testimony, that it was a bright, sunny day and that his wife and children were swimming in the Air Academy’s open air pool at the time of the attack.

The Kristóffy telegram shows that it wasn’t in the Soviet Union’s interest that Hungary be drawn into the war so, even given that the bombs dropped on Kassa bore cyrillic characters it could only have been, as in the case of the two other mistakes that day at Raho and Alsóverecke, an error by the Soviet Air Force. However, this option [lost Soviet aircraft attacking mistaken targets] is contradicted by the lack of insignia which must have been painted over. So, the attack must have been planned and it couldn’t have been carried out by Soviet aircraft. The aim of this webpage is to show how this event led to the declaration of war against the Soviet Union.

That afternoon, at around 2.20pm, the only report received at the National Air Defence Headquarters [OLP] about the bombing in Kassa was a phonecall from Miskolc, 54 miles to the south of Kassa, this, according to the National Headquarters, did not include any information about the identity of the planes only informing Budapest that communication with Kassa had been lost.[17] The telephone and telegraph channels in the Headquarters of the Kassa Air Defence were only repaired late that night. At 9.40pm Kassa sent a summary of the day’s events which stated about the aircraft only that the insignia could not be identified.[18] At some point after 2pm Major General Nándor Komposch, Commander of the OLP, presumably after receiving that first phone call from Miskolc Air Defence, informed his department heads that Kassa had been bombed by Soviet aircraft.[19] So, the leader of the OLP, having failed to confirm the information, intentionally or otherwise, forwarded this misleading information to his officers. However, it is beyond question that, as the leader of the Air Defence, his main task was to ensure the safety of Hungarian cities and to prepare for possible air raids, regardless of the nationality of the enemy so, acquiring confirmation on the validity of these reports was, strictly speaking, not his responsibility. At the same time, just before 2pm,[20] so presumably even before the phone call from Miskolc, the Head of the General Staff, Henrik Werth, was already in the Royal Palace informing the Regent that Kassa had been attacked by the Soviets. According to Horthy’s memoirs, he even referred to an investigation of the case, however we know that there was no such investigation on that day in Kassa.[21] Not only was there no investigation, but the headquarters of the General Staff failed even to get in touch with the Kassa Air Defence Unit. Wherever Werth got the information - presumably from Miskolc – he, unlike the head of the OLP, was responsible for getting confirmation of the news before forwarding it.[22] The Regent, who had himself been a military officer, didn’t order any further investigation. Given his nineteenth century military education, Horthy could not have imagined that a subordinate might lie to or mislead a superior in such matters. He considered the information as fact and dealt with it as such. Werth would have been completely aware of this. In the foreword of the published records of Prime Minister Bárdossy’s trial as a war criminal in 1946, Pál Pritz highlighted that during the trial the court looked at the telegram from the perspective of the 24th June and the bombing of Kassa and failed to note that before this date it carried much less weight. He was clearly right. On the 23rd of June the telegram was only a friendly message, an Empire’s promise, and not unique. Hungary had received numerous friendly promises from different Empires in its history most of which had never been kept, the telegram was considered in this light. Probably this is the answer in the long debate as to which memoir is right, the Regent’s, which accuses Bárdossy of keeping the message from him, or the Prime Minister’s, where he denies having done so. This interpretation seems to be confirmed given that Bárdossy did not state, even in his trial, that he forwarded the telegram to Horthy, he simply said that it was not hidden by him and he added, at the court, that the Kristóffy telegram was seen by several cabinet ministers none of whom considered it important to bother the Regent with.[23]

We would like to point out that on the 26th June at around 2pm, shortly after Werth’s departure, Bárdossy arrived at the Royal Palace and Horthy told him that [a] the bombing of Kassa had been carried out by Soviet aircraft and [b] that, as a result of which he had decided that such provocation could not be ignored and therefore war was to be declared on the Soviet Union. He asked the Prime Minister to make all necessary arrangements. At this point the contents of the Kristóffy telegram become key, Werth couldn’t be right and the bombings in Kassa shouldn’t have been taken as the reason for going to war. It is probable that Bárdossy didn’t even mention the existence of the telegram at this point. In his memoirs, Antal Ullein-Reviczky, head of the press department in the Foreign Ministry, recalled Bárdossy, shortly after his return from the Royal Palace, slumped in an armchair staring vacantly. “I told him that ’as far as I know, it has never happened before that peace turned to war in five minutes’”. At any other time Bárdossy would certainly have thrown me out of his office, but that day he simply answered in a low voice, ’what is it you don’t understand? That the Russians attacked us?’. ‘But is it certain that they were Russians’ I asked, and he answered: ’As the head of the General Staff and the Germans concluded that they were Russians and convinced the Regent it was them - that was it. It’s impossible to avoid war, especially as Romania is already in it. As you say, I understood it in five minutes’ with which he implied that he didn’t have any choice but to accept the decision.

Kassa had been cut off for the whole day the personnel of the Air Academy were not aware of the wider implications of the bombing – so officers at the airbase, except the one on duty, had gone home as usual. Bárdossy was still haunted by doubts about the identity of the aircraft late that evening. At 10pm, as phone contact with Kassa was finally re-established, he personally contacted the Academy and posed the question of whether the aircraft ’were Russian or German’, Lieutenant Jenó Chirke, the on-duty officer, replied that he ’didn’t know what kind of aircraft had attacked, the most precise answer he could give was that ’they weren’t German built.’[24] Bárdossy’s obedience, his acceptance without question of Werth and Horthy’s decision, originates in his diplomatic career where he was used to not questioning instructions from above.

So, this is the series of decisions and the route of information at the end of which the unidentified aircraft became Soviet and the war for Hungary was begun. We cannot say for certain when Hungary would have joined the war without Kassa, however we can certainly state that it could have been avoided at this point.

References

[1] A Moszkvai Magyar Követség jelentései, (Reports of the Hungarian Embassy in Moscow) edited by Peter Pásztor, Szàzadvég, Budapest, 1992.188

[2] Miklós Molnár : Kristóffy József táviratai (Telegrams of József Kristóffy) in: História, 1999, 21. vfolyam, 1. szám, 32.

[3]Antal Nàray visszaemlékezése, (Antal Náray: memoirs) sajtó alá rendezte, (edited by) bevezető tanulmányt és a jegyzeteket írta (foreword and references are written by) Sándor Szakály Budapest, 1988. 58 - 59.

[4] Bárdossy László a népbíróság előtt ( László Bárdossy at the People's Tribunal) , szerkesztette (edited by): Pritz Pál, 1991.145.

[5] Akten zur deutschen Auswertigen Politik 1918 – 1944, D-XII. 659.

[6] Péter Gosztonyi : Horthy, 1992. 38.

[7] Náray 1988, 59 - 60

[8] Géza Perjés : Bárdossy László és pere, in: Hadtörténelmi Közlemények, 2000. 4. szám. 792.

[9] UlleinReviczky 1993, 95. Idézi: Perjés, 2000. 792.

Lóránd Dombrády : Katonapolitika és hadsereg, 1920 – 1944, Ister, 2000, 141.

[10] Julián Borsányi: A magyar tragédia kassai nyitánya, München, 1985. appenix,I.4.(a).7.

[11] Horthy Miklós: Emlékirataim, szerkesztette: Antal László, Buenos Aires, 1953, ( A továbbiakban Horthy, 1953.) 251.

[12] Borsányi, 1985, appendix V.2.

Borsányi, 1985. Appendix, V.3.

Ibid, Testimony of József Ledényi

Ibid, Appendix IV,5.

„Szétfoszlotta reakció Bárdossy-legendája” – hogyan készítették elő a németek Kassa aljas bombázását – Krúdy repülőalezredes szenzációs leleplezése. In: Képes Figyelő, 1946. Március 16.

[13] Borsányi 1985, appendix, VI.2.

[14] Ibid Appendix, IV.3. számú mlelléklet, 1. oldal

[15] uo.71.

[16] Ibid Appendix IV.5,

[17] Ibid AppendixI.4.(a.)3.

[18] Ibid AppendixI.4..(b.)

[19] Pál Pritz: A Bárdossy Per (The Bárdossy case), Budapest, 2001. 39.

György Ránki: Emlékiratok és valóság (Memoirs and reality), Budapest 1984.l25.

[20] Pritz 2000, 39.

[21] Horthy 1990, 251.

[22] Antal Ullein-Reviczky : német háború, orosz béke (German War, Russian Peace), Budapest, 1993. 323.

[23] Pritz 1991, 10. Ibid 303. Perjés 1991, 819.

[24] Borsányi 1985, 61.

List of Photos

1.) Advancing German tanks in Operation Barbarossa - June 1941. Source: https://secondbysecondworldwar.com

2.) Henrik Werth, Chief of the Hungarian General Staff

Source: http://www.bibl.u-szeged.hu/bibl/mil/ww2/who/pics/werth.jpg

3.) Scene in Kassa after the bombing

Source: https://felvidek.ma/2016/06/legiveszely-kassa/

4.) Scene in Kassa after the bombing

Source: https://felvidek.ma/2016/06/legiveszely-kassa/2

5) Prime Minister Bárdossy at the Hungarian People's tribunal in 1946

Source: https://ntf.hu