Biography

Family life

He was born on the 18th June 1868, the fifth child of the Horthy family, in the county of Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok. In his early years he received all of his education in French from a native speaker. He was taught from the age of 12 in German at the College of the Reformed [Calvinist] Church in Debrecen, like many members of the Hungarian nobility of his age. On the 22nd July 1901 he married Magda Purgly de Jószási. [1]

They had four children. During the years of his marine officer career his family always travelled with him to his various postings. They were a very close family and his early letters show this and makes the tragic loss of three of his children all the more terrible. [2]

From her early childhood his eldest daughter Magdolna was sickly, she died of Scarlet Fever in October 1918 at the age of 16. His second daughter Paulette died in 1940 of tubercolosis. His eldest son died at the Eastern Front as a pilot on the 20th August 1942 at the age of 38. [3]

Career as a Naval Officer

At the age of 18 he entered the Royal Hungarian Naval Academy and studied there for four years. According to his memoir the Academy’s motto, Duty above life’, became his for the rest of his life. There were few young members of the Hungarian nobility at that time to have the opportunity to see as much of the world as he did. In 1886 he saw Barcelona and two years later, in 1888, he visited Holland. In 1893, on board the cruiser Saida, he sailed around the world. During this trip he saw the Arabian Sea, Bombay, Colombo, Bangkok, Borneo, the Solomon Islands, Malaya, Sydney, Melbourne, New Zealand and Batavia. From the description he wrote decades later it is clear that he admired the well organised bureaucracy of the British Empire. The impression he formed of the British Empire led to his strong belief, even during the Second World War, that it would be difficult to defeat the British.

In 1898, as a Lieutenant [Sorhajóhadnagy] of two years standing, he was sent to Britain to take delivery of a Destroyer, however, due to technical problems, he had to stay in the country for several weeks and he got to know London.

The years 1908 and 1909 had special significance in his life. His new posting was to Constantinople and at the time of the annexation crisis. This was when the Austro-Hungarian monarchy annexed Bosnia which, at that time, was legally a part of the Ottoman Empire. In July of 1908 the ’Young Turk’ movement, which demanded modernisation in bureaucracy and the political system, led to the downfall of the reactionary government. Coming to power, the Young Turks wanted to reaffirm the position of the country in the Balkan region where their interests clashed with those of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. On the 6th October the monarchy, with the support of the Russian empire, annexed Bosnia-Herzogovina. The general feeling in Turkey turned against Franz-Josef. There were frequent demonstrations and Austro-Hungarian goods were boycotted. Horthy, as an Austro-Hungarian naval officer, regularly sent military and political reports to his superiors in the Naval section of the War Ministry in Vienna [Kaiserliche und Königliche Marinesektion]. His quite detailed dispatches were read at the highest level in the War Ministry. [4]

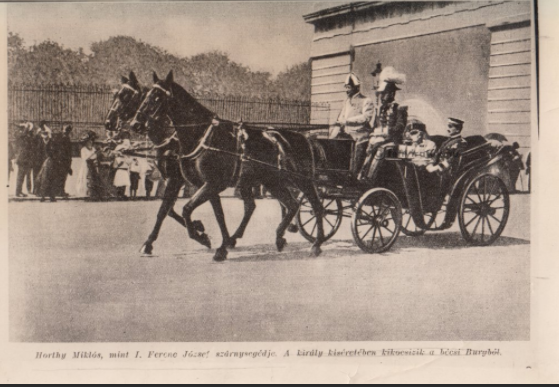

In June of 1909 Admiral Raimondo Montecuccoli, Head of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, recommended him to Emperor Franz Josef as a possible aide-de-camp and, in September 1909, he became ADC to the Emperor, a position he held until 1914. In 1933, Horthy recalled this period to Bálint Hóman ’it was just those five years which prepared me for my position today, I learned everything there, everything which has been most useful in the last ten years’. [5]

During Imperial audiences he was witness to political events, he became familiar with the bureaucracy and the organisation of the Empire, pan-Slavic ideology and the Italian separatist movement. He met people who would become significant in his future, among others Archduke Charles [the future monarch, Charles IV of Hungary and I of Austria] and István Bethlen. His political views, similar to those of the Emperor between 1904 and 1914, would have been described at the time as conservative liberal. He was a committed supporter of the Austro-Hungarian compromise of 1867 [a composition which established the dual monarchy of Austro-Hungary, the compromise re-established the sovereignty of the kingdom of Hungary, separate from and no longer subject to the Austrian Empire] he was against the idea of a Republic and opposed radical social reforms.

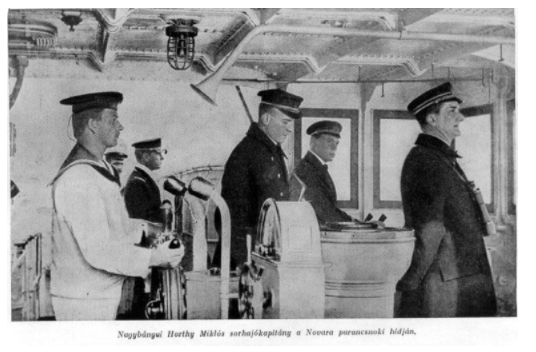

At the beginning of the First World War, Horthy was ordered back to the fleet and in the first month he commanded the destroyer Habsburg. The home port of the fleet was at the Naval base in Pola. In October 1914 the Entente powers built a barricade on the Adriatic, near the port of Otranto, to block movements of German U-boats to the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. In the May of 1915, commanding the cruiser Novara disguised as a steamboat, Horthy successfully towed a U-boat through these waters. For this operation he was awarded the Austro-Hungarian Military Order of Bravery [Third Class] and with the Iron Cross. Horthy had been arguing for months with the Admiralty for an attack on the blockade to clear Otranto Bay and, on the 4th May 1917 under his leadership, three cruisers sailed from the port of Cattaro: the Novara, the Saida and the Helgoland, and two Hungarian destroyers, the Csepel and the Balaton. Fourteen armed trawlers of the 47 forming the blockade were destroyed by the fleet, three were seriously damaged and a fourth was hit. Thanks in part to the times and to the ethics of the two Royal Navies, casualties were kept to a minimum and just 9 were lost or injured. According to British sources the crew of the Novara ‘allowed time for the crew of the trawlers to abandon their ships and held fire on the lifeboats’ these seamen were taken prisoner on the Novara and were treated courteously and, when an officer died, Horthy arranged for a burial with full military honours and flowers. [6]

On their way back from Otranto they were attacked by a British fleet out of Brindisi. The main allied naval base in the Adriatic at Brindisi had been informed of the battle in Otranto by the base there. In order to retaliate Horthy had to compensate for his shorter firing range by creating a mist of steam generated by the ship, allowing the Novara to approach unseen. During the subsequent battle, which lasted several hours, the Novara was seriously damaged and Commander Horthy badly wounded, though he insisted on staying at his post on a stretcher until he became unconscious. Although the success of the operation was incontestable - access to the Mediterranean was clear for a period - they failed to destroy the blockade completely and it was rebuilt in a month. So, the Battle of Otranto was an operation with a specific aim carried out by a talented naval officer. On the 1st February he was appointed to the post of Commander of the destroyer Prinz Eugen which he took over two weeks later. Also on the 1st there was a mutiny of ordinary seamen in Cattaro, the home port of the Austro-Hungarian state. It’s commonly believed in Hungary that the cruel reprisals that followed were ordered by Horthy, although at the time of these executions he was still in his previous post on the Novara in Pola. The crew of the Prinz Eugen was also on the verge of rioting, the war was clearly lost for the German Empire and its allies, delays in the payment of salaries, the breakdown in supplies and the internal ethnic conflicts in the Austro-Hungarian Empire had a significant effect on the army, and therefore the navy, and the crew was not far from rebellion. However, thanks to Horthy’s firm command, the crew’s dissatisfaction did not result in mutiny on his destroyer. Presumably it was this firmness that convinced Emperor Károly IV that Horthy was the man to cope with the rising dissatisfaction in the fleet. This explains why he promoted Horthy to the rank of Rear Admiral and put him in command of the Austro-Hungarian fleet ahead of eighteen Navy officers senior to him in rank. [7]

Way tothe Regency, and the early years as head of the state

The impact of a long-lasting war and the enormous social differences, intensified by the subsequent unprecedented depression, resulted in a popular uprising, not only in Hungary but in most of the defeated nations. Budapest wasn’t alone, Vienna and Berlin faced a very similar situation. Károly IV ‘relinquish[ed] his rights to participation in the administration of the state’ in both countries of the Empire. On the 16th November 1918, Hungary announced its independence from Austria and declared itself a republic. The first coalition government, appointed by Count Mihály Károly, reformed the law to broaden the franchise, giving the vote to every Hungarian citizen over 24 years of age and living at the same address for the previous six years. They also started thorough agrarian reforms, including land distribution. [8]

In the final months of the war soldiers in retreat after several years fighting on the front, were faced with a situation in Budapest and across the country similar to that in Germany at the time: rampant inflation and depression. On the 31st October, István Tisza, Hungary’s former Prime Minister and responsible for taking the country into the war, was murdered by soldiers not yet disarmed following their return. Partly in response to this the government decided to demobilise the Hungarian forces - five months before the ceasefire was signed.

On 20th March 1919 the government received the conditions of the armistice which included neutral zones stretching from the border deep inside Hungarian territory. In the final peace agreement this defined the new outline of Hungary and meant that the country lost two thirds of its territory. President Mihály Károlyi, Prime Minister Dénes Berinkey and his ministers resigned. The Hungarian Communist Party came to power led by Béla Kun. There was a brief dictatorship. As the power of the communist party was limited mainly to the capital, a separate department was founded to organise the taking of hostages from the most influential families in both Budapest and further afield. Enemies of the system were interned and an armed unit, the so-called Lenin-Fiúk [Lenin Boys], of the communist party terrorised the countryside with the massacre of civilians suspected of opposing the regime. Led by Tibor Szamuely they moved quickly around the country in a private train fortified with weaponry. In the May of 1919, with the tacit consent of the Western Allies, Czechoslovakia and Romania launched a joint attack on Hungary, thanks to rapid mobilisation the forces from the north were repelled, however by the 1st August Romanian forces had occupied and looted the capital and marched on into north-west Hungary. The communist regime failed and the leaders fled to Austria. Between January and August of 1919 Hungary had nine governments, four from the left and five from the right under the Regency of a Habsburg Archduke, none of them was confirmed or accepted in the international forum. Part of the country was occupied by French forces. [9]

On the 30th October 1918 the monarch ordered Horthy to hand over the fleet to the Allies. Following this action the Admiral travelled to Budapest for further orders from the new revolutionary government, but István Friedrich, the freshly appointed chairman of the military council, reprimanded him for having ‘betrayed his country’ in this way. Horthy withdrew to his estate in Kenderes. [10]

Meanwhile two separate but ideologically similar ‘ellenforradalmi’ [counter revolutionary governments] were formed in Vienna and in the Hungarian city of Szeged. The first, under the leadership of Count István Bethlen, united with the second, led by Count Gyula Károlyi and formed a cabinet in Szeged in the French-occupied southern zone of Hungary with the agreement of the French and the Serbian governments and of the Western Allies.

A group of military officers, under Gyula Gömbös began to put together an army for this political movement and, as Horthy was the highest ranked and most famous Hungarian military officer, Gömbös started recruiting in his name. Horthy arrived in Szeged in the spring of 1919 and was invited to lead this army and accept the position of Minister of War in the Károlyi government. On the 12th June Horthy stood down from his position in the government and became the commander of the Ellenforradalmi Nemzeti Hadsereg [the Counter-Revolutionary National Army]. In the August of 1919. when the Romanian army left Budapest and marched towards north-west Hungary, Horthy moved his army from Szeged in the south to western Hungary. During this movement the troops crossed the Alfőld [the main plain] of Hungary between the Tisza and Danube rivers. During this operation some of the unit leaders, Pál Prónay, Gyula Ostenburg and Iván Héjjas to name the most prominent, carried out reprisals which, as the leaders of the communist government had already left the country, meant public executions of mostly innocent civilians, local leaders and supporters of the previous regime. There is no source suggesting that Horthy gave orders for these actions and it is quite possible that he didn’t even know about them.

In the middle of August the army arrived in Siófok, a city on the shores of Lake Balaton in the west of the country. In the second half of the month, British Major General Sir Adam Clark arrived in Budapest to lead negotiations to form a government acceptable to the Western Allies in the peace negotiations at Versailles. As the leader of the only Hungarian army at the time, Horthy was also invited to these negotiations during which the participants agreed that a general election would be called and that, in the interim, a coalition government would be formed. Before the election Horthy would be allowed to march into Budapest and take the city over. On the 16th November, Horthy and the army entered Budapest and a coalition government , acceptable to the allies, was formed on the 23rd of the same month. On the 16th February 1920, the Hungarian Parliament declared Hungary a kingdom and revoked all laws of the communist legislation. [11]

On 1st March a law [I/1920] was enacted stating that a Regent would lead the country until such time as Charles IV and his descendants could be reinstated. According to this new law the Regent would have limited rights compared to those of a King. Unfortunately no copies of the initial drafts of this law survive. The political system was not so different from that in Britain where the Royal Family holds the title of monarch through succession. The monarchs of Hungary were the Habsburgs, but the Western Allies would not countenance a Habsburg leadership either in Austria or in Hungary to ensure that the old empire could not be revived. [12]

On the 3rd February 1920 the Council of Ambassadors [a meeting of foreign ministers of the Western Allied Powers in Paris] declared that they would not accept the Habsburg monarchs either in Vienna or Budapest. Officially Hungary considered the Habsburgs to be their legitimate and sole leaders, however they were aware that, given the political atmosphere, a Habsburg monarch could not be crowned. As a result the decision was made to elect a regent for the period of the Habsburg family’s enforced absence. [13]

And so, on the 1st March 1920, 131 of the 141 members of the Hungarian parliament elected Horthy to the position of Regent [II/1920]. [14]

However, immediately after the election Horthy called for a re-negotiation of the rights accorded to the Regent, feeling that, as it stood, there were too many restrictions to govern the post-war country effectively. The bill was re-negotiated and in the final version most of the rights of a monarch were retained for the new post with some exceptions: the Regent could not confer nobility; he did not have the right of patronage [the nomination of clerics]; he could not name his successor and he did not have the right of Royal Assent which meant that laws could be enacted without his consent. Horthy accepted the post.

Charles IV made two attempts to return to Hungary in 1921. The first time, on 27th March 1921, he arrived incognito Szombathely in Western Hungary. Pál Teleki, who was hunting in the neighbourhood, at the estate of Count Cziráky Dénes, was informed of the King’s return in the middle of the night on Easter Sunday and immediately set out to see him. He was confirmed in his position of Prime Minister. That same night a second government was formed and in the morning, with the news of the King’s return and the political developments of the night, Teleki was sent to the Royal Palace in Budapest to prepare the Regent for the King’s arrival. Unfortunately he became lost and ‘had a puncture’ en route, so the King arrived unannounced at the Royal Palace, finding the Horthy family at lunch. In their brief meeting Horthy informed him of the decision of the Western Allies and asked him to leave Hungary before neighbouring countries attacked. [15]

Teleki finally arrived after the King had left the capital.

The King returned to Switzerland. However, on October 21st of the same year, Charles attempted once again to take back power. This time there were serious military preparations in western Hungary in the estates of aristocrats loyal to him. Arriving in Hungary he travelled to the capital by train. Most garrisons along the route pledged their allegiance because they believed that his return was with the consent of the Hungarian Regent and government. As it was a Sunday and the King was a devoted Catholic he stopped at every station for Mass, this time was sufficient for the capital, the Regent and the government to build up their defence, concentrating troops in the area of Budaörs, these units consisted mainly of voluntary groups of university students.

Both sides wanted to avoid fighting. The King’s commanders took positions for their troops around Budaörs such that a serious battle was physically almost impossible. The King himself did not believe that he would encounter military opposition, and, appalled at the idea of a battle against his own people, ordered a retreat. On the way back he was taken into custody by the Hungarian authorities and held in the monastery at Tihany next to Lake Balaton. He was subsequently transported by the Allies and held under house arrest on Madeira where he died of the Spanish ‘flu 6 months later. [16]

Two weeks after the King’s failed second attempt, on the 6th November, the Hungarian parliament enacted a law governing the dethronement of the Habsburg monarchy [XLVII/1921] declaring that the Habsburg monarchy had lost its right to leadership in Hungary. [17]

Admiral Nicholas Horthy was regent of the Hungarian Kingdom until 15 October 1944. The main stages and controversies of his activity in these years are discussed separately. Please look up them in the main menu.

After his resignation

On 17th October 1944 the Regent, together with his wife, grandson, daughter-in-law and his closest family employees were taken into custody and transported to Germany where they were held as prisoners of war by the SS in the castle of Count Hirschberg in Upper Bavaria. They were cut off from all news of the war until January 1945 when the newly arrived, younger brother of the Regent managed to smuggle a radio into the castle. Using this the family could secretly listen to allied broadcasts. [18]

On the 1st May 1945 soldiers of the 7th US Army were the first to arrive in the area of Weilheim and Schloss Hirschberg. The SS unit had left a few days earlier. [19]

On this day Miklós Horthy’s American custody began, at first he was taken to a mansion on the outskirts of Augsburg where his first interrogations were recorded. It was here, on the 9th May, that he was informed that his son Miklós was alive and had been found by the American army. The former Regent was transferred to a prisoner of war camp in Belgium where former members of the Hungarian Arrow Cross leadership were also held. This was where he was first informed of the apocalyptic siege of Budapest a few months earlier in the winter of 1944-45. [20] During that year he was held at several POW camps: Lesbois, Mondorf, Wiesbaden, Oberursel and Nuremberg. [21]

Joseph Stalin was, from the beginning, against the request of the new Hungarian government to arrest Horthy as a war criminal and give him up to the Hungarian authorities. As far as he was concerned his decision was purely political. The period 1920-1944 is identified with the name of Horthy, the official press echoed with his name, the name of a national hero. If he had been tried, sentenced and executed at least a part of Hungary would have regarded him as a martyr and this was the last thing the Soviet leader would want in a country occupied by the Red Army.

The first interrogation was held on the 27th August 1945, he was asked about Hungary’s war declarations, the details of its participation in Germany’s operations, the peace negotiations and the anti-Jewish legislation in Hungary. [22]

A month later, on the 27th September, the former Regent was transferred to Nuremberg together with other notable prisoners of war [Franz von Papen, the former German Ambassador in Turkey, among others], where he was no longer treated as a war criminal but as a witness. Here he was asked primarily about his negotiations with Hitler.

On the 1st December 1945 he was allowed to meet his son whom he hadn’t seen for more than a year and after this was allowed to see him regularly. On the 17th December he was released.[23]

1) Nicholas Horthy as aide de camp of Emperor Franz Joseph

2) Children of Nicholas Horthy

3) Admiral Horthy in the battle of Otranto

4) Scene of the Tisza-murder. Source: 24.hu

5) Election of the Regent, 1 March 1920. Source: Újkor.hu

6) University Students in the battle of Budaörs. Source: Konrád Salamon: A csonka ország, Budapest, 1994.40.

References

[1] Miklós Horthy: Emlékirataim, Budapest, 1990. 9 – 40.

[2] Horthy Family Archive, II.5.2. / közös tételes / Horthy Miklósné levelezése Horthy Miklóssal / 1914 – 1918.

[3] Horthy Family Archive, II.5.2. / közös tételes / Horthy Miklósné levelezése Horthy Miklóssal / 1914 – 1918.

[4] Dávid Turbucz: Horthy Miklós, Budapest 2011, pg 38

Horthy 1990, 33-50.

Turbucz 2011, 41.

Péter Sipos: Előportré a névadóhoz. Horthy Miklós, a tengerésztiszt. In: Világosság, 1993/6 ( XXXV.) 24.

[6] Mark Kerr : The Navy In My Time, London, 1933 196.

[7] Gusztáv Gratz: A forradalmak kora. Magyarország története 1918-1920. Budapest, Magyar Szemle, 1935. 3.

[8] Ignác Romsics: Hungary in the twentieth century, Budapest, 1999. 89-99.

[9] Ibid 99 – 108.

[10] Gergely Bödők: Vörös és fehér – Terror, retorzió és számonkérés Magyarországon, 1919-1921. In Kommentár: 2011/3. Pg 27.

[11] Romsics 1999, 102 – 125.

[12] Decree Nr I./1920 full text is published:

https://net.jogtar.hu/ezer-ev-torveny?docid=92000002.TV&searchUrl=/ezer-ev-torvenyei%3Fpagenum%3D38

[13] Decreee of The Council of Ambassadors in Paris on the return of the Habsburgs, 3rd February, 1920. in: Francia diplomáciai iratok 2., szerkesztette: Ádám Magda, Ormos Mária, fordította Barabás József, Révai Digitális Kiadó, 2007.

http://www.tankonyvtar.hu/hu/tartalom/tkt/francia-diplomaciai-2/ch02s06.html#I77

[14] Decree II / 1920 full text is published:

https://net.jogtar.hu/ezer-ev-torveny?docid=92000002.TV&searchUrl=/ezer-ev-torvenyei%3Fpagenum%3D38

[15] Mária Ormos: "Soha amíg élek" - az utolsó koronás Habsburg puccskísérletei 1921-ben, Pécs, 1990, 51-60.

Karl Freiherr von Werkmann: A madeira halott, München, 1923. 120-155.

[16] Ibid 260.

Aladár Boroviczény : A király és kormányzója, Budapest, 1993, 444.

Decreee XLVII / 1921

Full text available:

https://net.jogtar.hu/ezer-ev-torveny?docid=92000002.TV&searchUrl=/ezer-ev-torvenyei%3Fpagenum%3D38

Horthy Miklósné: Napló, 1944 – 1945. Szerkesztette: Bern Andrea, Budapest, 2015. 42-43.

Uo.60-65.

[20] Horthy 1953, 338.

[21] Uo. 335 – 349.

[22] Gellért Ádám – Turbucz Dávid: Egy elmaradt felelősségrevonás margójára, in: Betekintő 2012/4, 10-12.

[23] Ilona Edelsheim Gyulai, Honour and Duty, Purple Pagoda Press Ltd, Lewes, 2005, pg. 327 – 332., Catherine Horel: L’amiral Horthy, Párizs, 2014, 368.